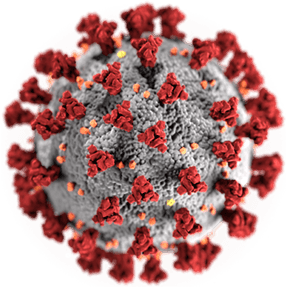

On March 11, 2020 the World Health Organization (WHO) declared Covid-19 as a pandemic. A quickly evolving phenomenon across nations, so far thousands are infected and hundreds have died from it. Needing a reference point, we have resorted to comparing this to the closest thing we know in viral epidemics- the flu. As of today, only a few months into the pandemic, Covid-19 can’t hold a candle to the flu virus that kills thousands every year. However, unlike the flu, this is a novel human virus for which we don’t have years of epidemiologic and clinical data that helps us to understand or predict how this pandemic will unfold, how to best treat it and most importantly we don’t have a vaccine for this one-yet.

For all its novelty though, this scenario is déjà vu all over again. What the world is feeling now is close to how we were feeling around the time another novel virus, Ebola surfaced among us and claimed the lives of more than 11,000 West Africans between 2013-2016. For the relief of the western world and the WHO, that regional epidemic remained to be pretty much an African continent problem, having only achieved the status of “Public Health Emergency of International Concern” on August 8th, 2014. The scramble to contain the spread of Ebola was filled with unforgettable chaos and horrific scenes. The outbreak also laid bare the dangerous vulnerability of that continent to public health calamities and exposed the dismal resource shortage and basic infrastructure of many African nations. Despite scoring some of the highest GDPs during that period we watched with a sense of grief and anger the evidence that developmental agendas in most African nations did not seem to have prioritized basic public health needs such as having access to water, waste disposal system and sanitary conditions in health facilities. Neither the available resources nor the number of local healthcare workers who were putting their lives on the line were a match to the fire that was raging. Healthcare workers from western institutions not only designed personal protective equipment but also traveled to Africa to help teach the ‘magical’ principles of hand-washing, contact precautions, and disease transmission.

Well, here we are again. We have yet another novel intruder among us and it too thrives among crowds, and poor hygiene, and targets those with poor defense mechanism, be it from illness, old age, malnutrition or lack of access to healthcare. Covid-19 is in Africa and the low numbers reported thus far is likely a reflection of the limited testing capacity of countries than the true regional prevalence. The work that is ahead is enormous as is the information that is coming out from various sources.

Below I have compiled some general public health recommendations that I feel need emphasis in the African context based on years of experience as a physician, public health and global health practitioner as well as health policy educator. Readers should also refer to CDC.gov and WHO.int for more specific and up to date information on the topic.

Community education: using multi-media outlets, billboards and other methods of posting informatics, start massive dissemination of basic but science-based facts about this virus, including directly addressing false narratives about the virus. This is cost-effective, can be locally resourced and can be done now.

Focus on human resources: recruit and give accelerated training to large numbers of lay personnel (a few hours to start with and then reconnect for updates daily as needed) and deploy them among communities to enforce the education. Appointing a lead person among social groups, community organizations including churches, mosques and other religious entities to be the ‘czars’ in educating their constituents is a powerful way to reach those who may not access media-based education. This investment in local human resources will likely initiate many for future similar needs (if they were to arise) and might become the impetus for the culture to embrace sound public health principles that is helpful for healthy communities.

Crowded spaces: in nations where thousands rely on crowded public transport every day or live in crowded spaces, implementing social distancing principles is a real challenge. Some potential interventions that might be helpful is to encourage able body adults to walk to their destination where possible, to limit the number of persons allowed in a vehicle, encourage employers, schools and religious institutions to devise ways for people to work/learn and worship from home where possible. The issue of crowds in business centers, such as in open markets and in the dwelling quarters of the homeless and inadequately housed citizens is a particularly sensitive area and requires local forethought. Policy makers must make allowance to not do undue harm to individuals while trying to protect the larger public. This will be one of the angsts of public health interventions of large scales and requires dialogue and compromise.

Healthcare workers: equip healthcare workers to adequately protect themselves first. Making water, sanitizing gels/wipes and face masks available in healthcare facilities should be one of the first priorities of the intervention. Give clear and standardized recommendations on how to deal with the outbreak by requiring training for all healthcare workers throughout the country. Post flowcharts, and algorithms and other resources readily visible and available in practice areas so that busy practitioners’ workflow is efficient.

Standardize approach to screening and management: frontline workers should be clear and trained to identify the difference between ‘testing’ and ‘screening’ and appropriately triage patients so that clinical practitioners’ times are protected for clinical evaluation and treatment. Currently, no screening for Covid-19 is recommended (except in special cases such as where a person may have come in direct contact with another person who has the disease) but testing those with symptoms is recommended for suspected conditions. The appropriate use of limited resources is another critical public health principle as governments prepare to provide the timely testing needed for those with concerning symptoms.

In the event of massive spread: no one nation can handle disasters of large scale on their own and collaboration will be needed, but governments need their own task force and a command post that can spearhead disaster preparedness, coordinate efforts, and monitor progress- they need that now, and not after disaster unfolds. China built several temporary hospitals to contain the influx of Covid-19 patients within weeks of the outbreak. The budget and the resource of African nations may not be there to build temporary hospitals but conversations should be had in regards to alternatives such as makeshift structures, and tents if hospitals get overwhelmed by patients.

The work of public health, containing the emergence and reemergence of new and old epidemics across the globe, is like the work of Sisyphus- no sooner do you get the big boulder up to the top than it begins to roll back down the hill. This pandemic will pass but others will come. Are African nations prioritizing their money and resources where it matters the most? Are donor agencies giving the right accolade for development and incentives for recipient nations in order to prioritize basic human needs? Do private investors and philanthropists who participate in African development agenda have public health matters on their radar screen?

So far, we have seen little evidence that is the case but it is never too early to ask these questions- even when in the midst of a disaster at hand.

Sosena Kebede, MD, MPH

Baltimore, Maryland, USA